The Most Powerful Practice for Academic Growth

/Help students develop a growth mindset with a few simple steps.

Read MoreHelp students develop a growth mindset with a few simple steps.

Read MoreWe’re only 3 months into 2020 and schools are now closed, many for the remainder of the year, in an effort to slow the spread of COVID-19. As a tutor who primarily works with students online, I’ve heard from parents and students about the difficulties they’re facing with the unanticipated switch to online/distance learning. It’s been a tough time for everyone, and as we’re increasingly homebound, I’d like to give some tips to parents and students to make online/distance learning more manageable..

Also, click here for a free organizer you can use to help minimize confusion over when and how to access class materials and turn in assignments.

Some of the more frequent complaints I’ve heard?

Lack of the usual in-person coordination between teachers means work is often unevenly distributed during the week, with many hours of work assigned on one day and very little the next.

Inconsistent delivery of assignments and materials. Some teachers are emailing while others use Google classrooms, etc. Some post daily while others post less frequently.

Lack of clarity on how to turn in assignments. Inconsistency in delivery instructions.

Lack of motivation on the part of students. Feeling like it “doesn’t count.” Boredom/fatigue.

Here are some tips for parents and students to make things more manageable. For younger students (and older students struggling with motivation), parents will need to be more involved.

-Class name

-Teacher’s delivery method for materials and assignments

-Days/times when teacher will post or send materials/assignments

-Student’s delivery method for completed assignments

Click here to download a free organizer you can use.

These days we might be even more glued to our devices than ever, which is why it can feel overwhelming to have assignments coming in periodically throughout the day. If teachers are doing live video classes, students know when to be connected, but if not, they may feel that they have to constantly check online platforms and email for new assignments. That’s why I think it’s healthier and more efficient to set daily check-in times for each class.

Based on when or how often teachers are posting or delivering materials, make a schedule of times to check online platforms, email, or to physically pick up materials from school, depending on your school and district.

Some students tend to let assignments pile up while others will try to do them all immediately as they come in. I think a more sane approach is to make a clear game plan for each day and for as many days in advance as possible. It’s mentally less draining to identify the tasks for the day and check them off than it is to be constantly connected and trying to do everything at once or to let work pile up and then panic.

Using outside materials to reinforce knowledge is always a good idea, but especially so when students are not getting the same amount of instruction or explanation as they would in the classroom. A simple place to start is with a Google search of the topic + “explanation” or “examples.” This of course requires more work and effort on the part of students, but my hope is that one very positive outcome of this situation will be that students emerge as more independent learners.

All of us, teachers, parents, and students, are struggling with technological overload in different ways, and even more so now that we are unable to do some of the activities we love. With gyms/studios closed and sports and music programs canceled, most of us are on our devices more than ever.

It’s so important to be mindful about our time spent on devices (as well as the content we’re consuming), and sometimes building in other activities is easier than trying to limit our scrolling of Instagram with nothing to replace that. While technology is helping us socialize safely via video calls and group chats, it’s crucial that students have other activities built in throughout the day to relieve stress and stay emotionally healthy.

As I went into my first year of teaching, I was far too overwhelmed to think about how I could consciously create a classroom culture. I did instinctively know that I wanted to establish an environment of trust, respect, and kindness, in line with my core values. But how to accomplish that?

As a more experienced teacher, I can now reflect a bit more on what a positive secondary classroom culture looks like and how we can build it. I also realize now that it’s not as hard as it may seem when you’re new to the classroom.

So what does a positive classroom culture look like? I define it as one that supports and enhances students’ learning, helps students take on challenges with a growth mindset, and promotes healthy social behaviors.

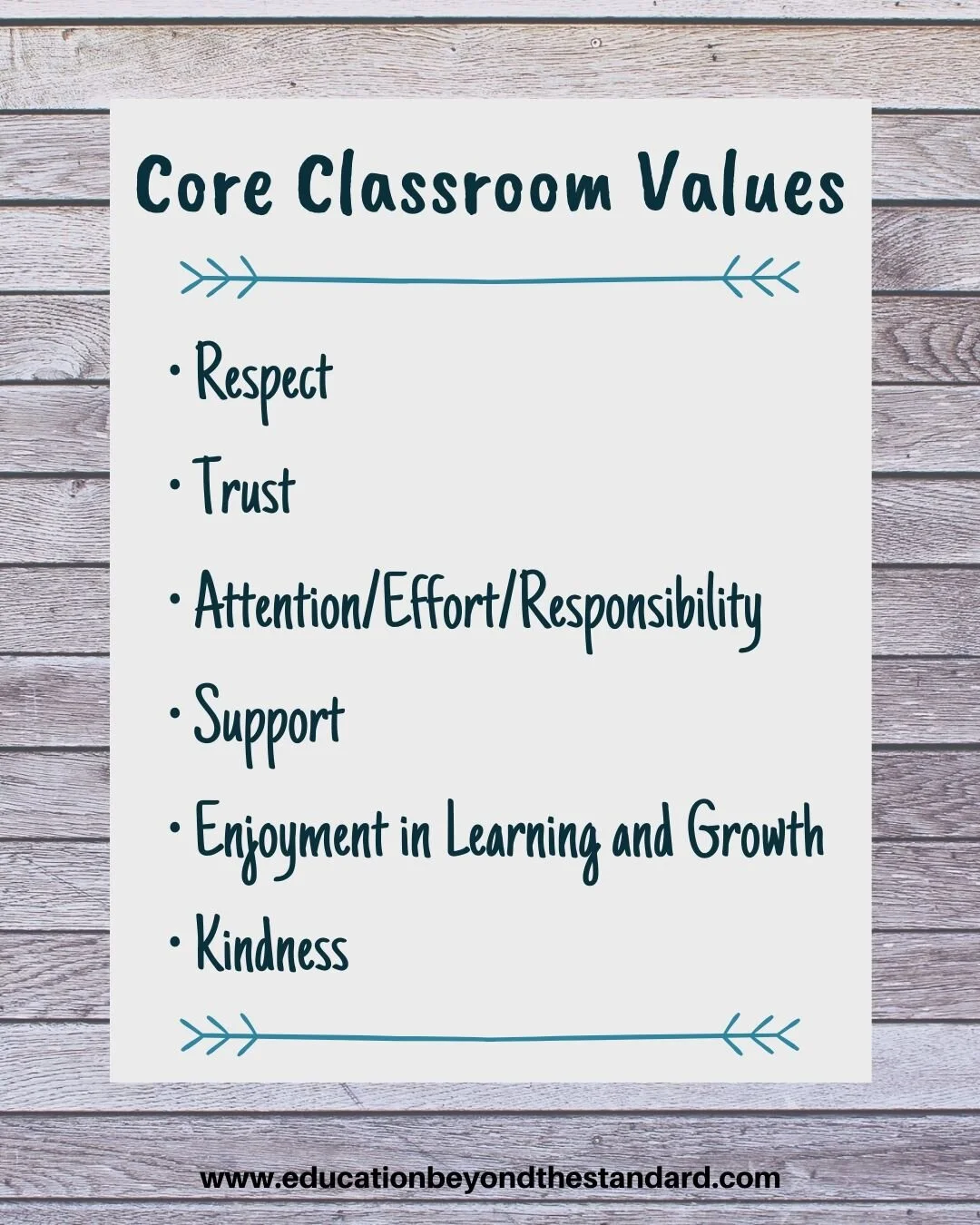

I think the first step in creating a positive classroom culture is getting to know our core values so we can be conscious about establishing classroom procedures, guidelines, and expectations that reflect them. What are some core values for the classroom that resonate with you? Here are a few of mine:

Respect

Trust

Attention/effort/responsibility

Support

Enjoyment in learning and growth

Kindness

Since I’m no longer in the classroom but still working with students as a tutor, I hear a lot about classroom cultures and management styles from students’ perspectives. Here are a few pieces of insight that I’ve gained from this experience:

Regardless of classroom management style, students can always sense (and always appreciate) when teachers truly care and are passionate about teaching.

Core classroom values such as trust, respect, and support start with teachers. Teachers who model these core values even in the face of behavioral issues lay the foundation for them to flourish in the classroom.

Consistently praising effort and improvement over perfection or traits like intelligence creates a supportive environment in which all students feel they can grow.

Clarity and consistency in the application of classroom rules and procedures helps to build a safe environment in which trust can develop.

Secondary teachers have the unique opportunity to “reset” students’ expectations about what a classroom experience can be. At the secondary level, kids are coming into the classroom with a wider variety of previous experiences in school, both good and bad. This means a greater variety of attitudes toward learning and ideas about appropriate classroom behavior.

With your core values and some student insights in mind, here are some thoughts for creating a positive secondary classroom culture, either from day one or to reset after a rocky period.

Communicate with clarity, warmth, and calmness what your expectations are. By communicating in this manner, you are modeling respectful, appropriate interactions and setting the standard for how you expect students to communicate in your classroom.

Put classroom rules, policies, and procedures in writing. You may even have students participate in the process of creating clear and fair policies.

Discuss the core values that you’ve identified and what they look like in action. Ask students to give examples of what each of the values looks like in action.

Provide clear, written academic expectations and policies, including late work, test retakes, extra help, and missed classes. Some of the most common issues I see with students I tutor involve these topics. You can avoid future confusion and disputes by clearly defining policies and students’ responsibilities from the beginning.

Have students sign all written policies and procedures to indicate they are in agreement with them.

If an issue arises that requires a change in classroom policies/procedures, discuss openly and clearly with students. As long as there is a clear rationale for the change, students will usually be on board.

Be authentic with students—if you make a mistake, acknowledge it. If a lesson or activity doesn’t go well, discuss it. Students don’t expect teachers to be perfect, and mistakes or bombed lessons can be a great opportunity for us to model accountability and authenticity.

Please let me know in the comments below if you have any tips or techniques for building a positive classroom culture at the secondary level!

Secondary curriculum in most schools and districts is meant to prepare students for university study, but it rarely prepares them for the exams that still play an important role in college admissions. Whether due to time constraints, the perceived difficulty of the material, or the idea that SAT/ACT material is incompatible with other curriculum priorities, SAT/ACT practice is often left to students to do on their own.

In this article, I’ll give you 5 reasons why incorporating SAT/ACT practice into your curriculum is a great idea, whether or not your school separately offers SAT/ACT prep courses or workshops. In a later post, I’ll give you some ideas for easy ways to do so.

When compared with the Common Core and other state standards, the SAT and ACT require a higher level of reading, language, and math skills. Not every topic or skill you teach will appear on the SAT/ACT, but where there’s an overlap, SAT/ACT questions generally go deeper and require more critical thinking and analytical skills. The reading passages are rich sources of academic and Tier 2 vocabulary. Math questions tend to require greater integration of diverse math skills and more complex problem solving.

Before I started tutoring and offering small group SAT/ACT test prep, I mistakenly believed that the SAT and ACT measured mastery of topics and content knowledge. As I began to understand the tests better, I realized that they are actually designed to measure academic skill.

While content knowledge is certainly a big part of doing well on the math portion of these exams, and vocabulary is important for the language portions, content knowledge only gets students so far. The rest comes down to skill: how well do students parse a text for meaning, argument, evidence, and structure? How well can they problem solve? How well do they think and write about a topic? These are skills that are crucial for students’ future academic outcomes.

All students are subjected to the same test, but unfortunately study after study confirms that socioeconomic factors play a major role in SAT/ACT scores. Building in some SAT/ACT-type practice to your curriculum is a great way to make sure all students gain familiarity with the test material and format.

I can personally attest to the truth of this one: when I mention to students that a particular math topic is tested frequently on the SAT/ACT, their ears perk up. What may have quickly been forgotten after a lesson or unit ends is now given a place of greater importance and is more likely to be remembered. Not every student will be motivated to pay extra attention to material they know might appear on the SAT/ACT, but many will.

For consistent early finishers and high achieving students, SAT/ACT practice provides a challenge and an opportunity to test and improve their skills. I love reinforcing crucial academic skills that are relevant to the topic at hand with “SAT/ACT challenge questions.”

I’m a big believer in the idea that all students (not just our self-motivated high achievers) benefit from challenging work that requires higher level thinking and problem solving, with the appropriate support and resources.

Please let me know your thoughts (and whether you include any SAT/ACT practice in your classroom) in the comments below!

With all of the many secondary English curriculum demands, it can be hard for teachers to fit in vocabulary instruction. Fortunately, building effective vocabulary instruction into your classroom can be relatively painless (low prep or no prep) and incredibly beneficial for your students.

Study after study confirms that vocabulary skill Is strongly correlated with academic, vocational, and social outcomes. (ASCD) This is likely due to the fact that vocabulary skill is a major component of reading, writing, and oral communication skills, which all play a significant role in these outcomes.

Vocabulary skill goes much deeper than memorizing definitions of words: it’s about how we use words to convey precise and nuanced meanings, how accurately we interpret meaning in language, and how well we understand the relationships between words.

The Common Core State Standards distinguish academic vocabulary (high-frequency words that may have multiple meanings) and vocabulary in context from domain-specific vocabulary (words that are associated with a specific subject, such as genome or treaty). This focus on high-frequency words and meaning in context is closely aligned with the skills tested on the SAT and ACT and those required for success on the university level.

Whether mandated by standards or not, teaching vocabulary at the secondary level is a powerful tool to improve students’ reading and writing skills, standardized test scores, and overall academic outcomes.

In many ways, teaching vocabulary at the middle and high school level is not that different than at the elementary level. Here are some characteristics of effective vocabulary instruction:

Small, manageable word lists (10 or less)

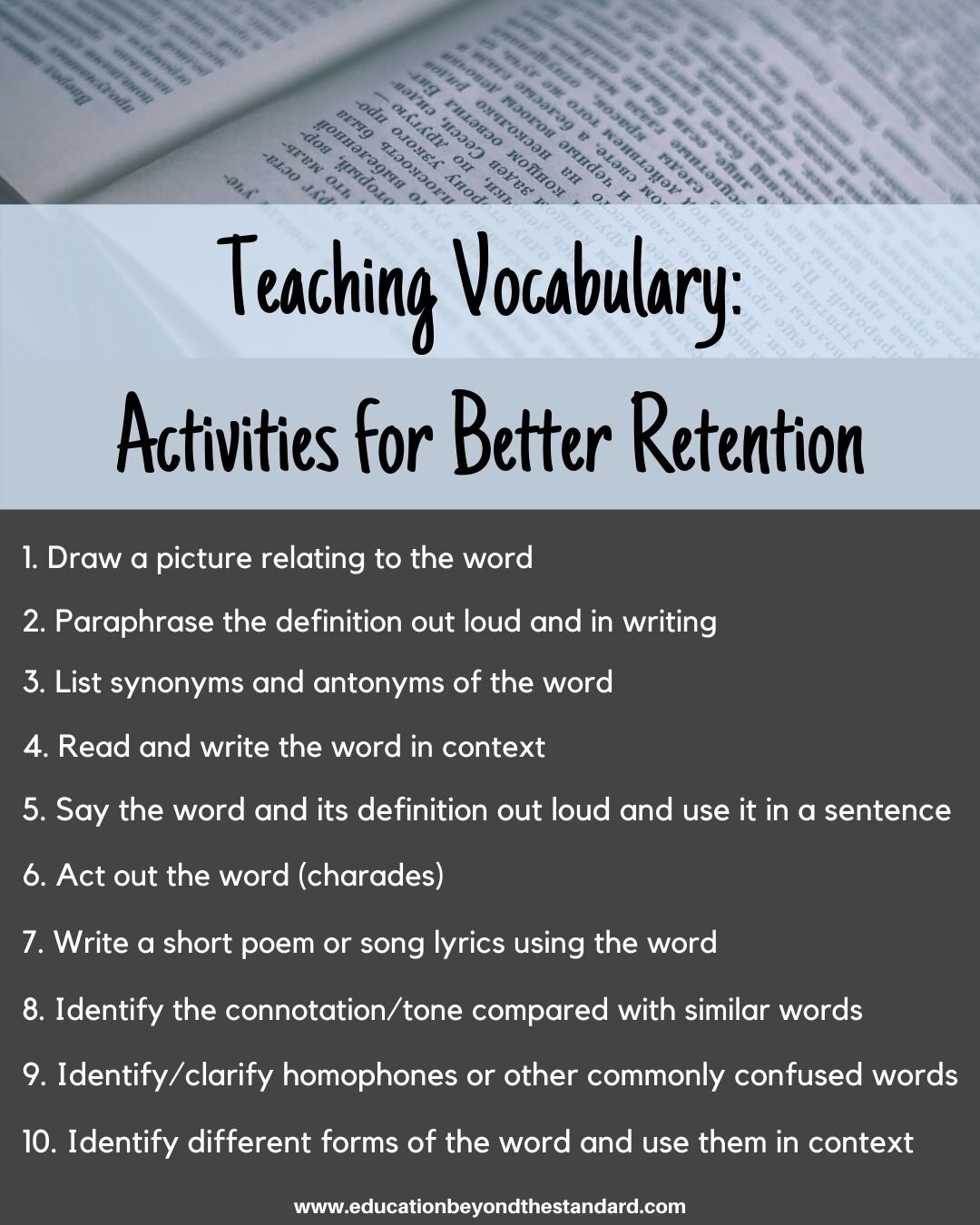

Varied learning methods and activities, including physical movement, visual aids, speaking/listening, reading/writing, drawing a picture, synonyms/antonyms, etc.

A focus on high-frequency words over very specific or technical words (domain-specific and technical words can be taught as needed for lessons on these topics)

An emphasis on context (both understanding words in context and using them correctly in context)

Of course our hope is that when students get to middle and high school they’ve already been exposed to and practiced good vocabulary learning strategies. We also hope that they come to us with grade-appropriate vocabularies. Unfortunately, for a variety of reasons, this may not always be the case. And research shows that the gap between students with broad, grade-appropriate vocabularies and those without tends to grow wider by the year, which makes effective secondary vocabulary instruction even more important.

There are many excellent stand-alone vocabulary systems that you can implement for a low to no-prep solution. I’ve created this year-long, 200-word vocabulary program, which requires no prep. You can also create your own vocabulary system to work within your novel and nonfiction text studies, although this option requires more planning on your part.

It’s important to evaluate what will work best with your curriculum, standards, and time constraints, and go from there. Both stand-alone vocabulary and vocabulary as part of a fiction or nonfiction text can be very effective, as long as the general principles described above are incorporated.

Understanding how words relate to one another is a big component of the higher level vocabulary skills that contribute to strong reading and writing skills. Knowing that neutral and indifferent have two different shades of meaning and being able to both identify why an author might choose one over the other and also choose the appropriate word for a given situation are examples of these higher level skills. Use class discussions to highlight different uses of words that achieve a certain tone or connotation. Ask students to come up with synonyms that have a similar tone or connotation.

If you go with a stand-alone vocabulary system, make sure it emphasizes academic vocabulary. If you choose vocabulary for each novel or text, try to ensure that the words you select are mostly academic vocabulary as opposed to domain-specific vocabulary. Of course if your class is reading a nonfiction text or novel with a heavy focus on a particular subject, you will need to include domain-specific vocabulary words. But generally speaking, students will get more mileage out of having a broader academic vocabulary than a narrow, domain-specific vocabulary.

Students will benefit from as much practice using vocabulary words (and hearing/seeing them used correctly) as possible. One simple way to do this is to keep a class tally on the board for the number of times each vocabulary word is used correctly in context during a class discussion. If a student uses a word incorrectly, it’s a great opportunity to discuss why its use was incorrect and the correction necessary.

While we hope that students learn these techniques in earlier grades, we can’t assume that all of our students will come to us already having this skill. Fortunately, the techniques aren’t too difficult or time consuming to teach and once we do, we can reinforce them throughout the year. I’ve created this no-prep mini unit to teach techniques for understanding vocabulary in context.

Give students vocabulary word activities, discuss words and their shades of meaning, and play vocabulary games to make vocabulary learning a lot more interesting and interactive than memorizing a word list. Here is a vocabulary bingo game I created that use homophones and frequently confused words (middle school edition). Of course students need to know the definitions of new words, but make it clear that that’s not the only goal, nor the most important. Improving our language abilities holistically is actually enjoyable and if we share that attitude from the start students will catch it too.

What strategies and methods have worked well in your classrooms? I’d love to hear from you in the comments below!

When it comes to college planning, many students and parents find themselves wondering if there’s a clear advantage in taking either the SAT or ACT. My usual advice is that the choice of test is less important than how much effort students put into mastering it. With that being said, there are some differences between the SAT and ACT that, for some students, may make one test preferable to the other.

The College Board and ACT conducted a concordance study for SAT-ACT scores and published a 2018 conversion chart, which can be used to determine what a given score will translate to from one test to the other. If students take both an SAT and ACT practice test, they can use the conversion chart to see whether their scores are basically equivalent or higher on one test. If they did do better on one of the tests, they can plan to take that one.

Note: the tests have changed since 2018, so this chart may not be very accurate anymore.

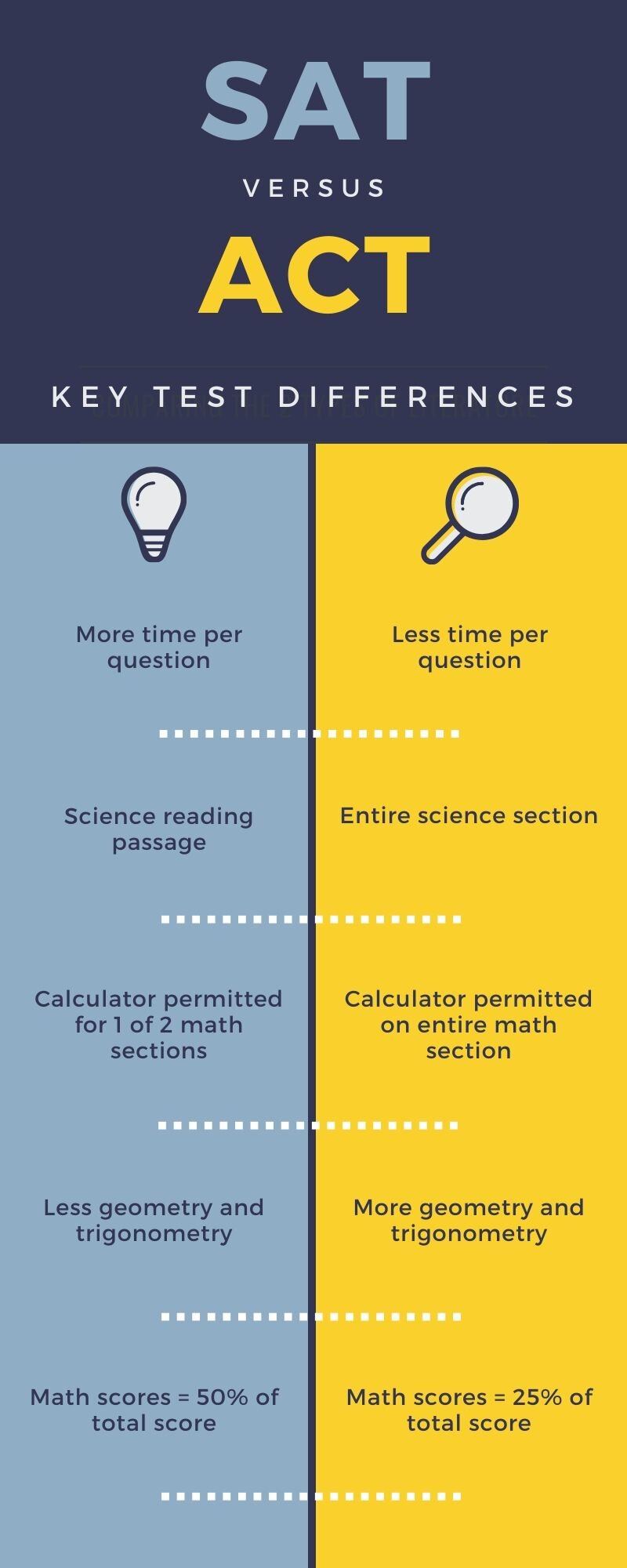

The SAT and ACT cover largely the same material in a pretty similar manner. However, there are some differences that may provide an advantage to some students.

The ACT has an entire science section (optional on the digital version) while the SAT contains science passages on the reading section. Neither the SAT nor ACT test your science content knowledge, but rather your ability to interpret scientific information that is given.

The pacing (time per question) on the ACT is faster than on the SAT. Students have to answer more questions in a shorter time on the ACT.

The SAT reading section gives questions in chronological order with the passage, while the ACT reading section does not.

SAT reading questions focus heavily on identifying evidence in the passage that supports a claim. Questions of this type don’t appear on the ACT reading section.

The SAT essay (50 minutes) asks you to read an essay and evaluate the structure, arguments, and evidence relied on by the author. The ACT essay (40 minutes) asks you to analyze different points of view on an issue, state your position, and support it with evidence. Both essays are optional but recommended.

The ACT math section tests some topics, such as trigonometry, more frequently and in-depth than the SAT math section does. However, some students find SAT math questions to be worded in a trickier way than ACT math questions, which tend to be a bit more straightforward.

The SAT has one math section that prohibits the use of calculators. The ACT allows calculators for the entire math section.

The ACT math section covers more geometry than the SAT math sections.

The SAT math sections provide a reference guide with some formulas, while the ACT math section does not.

Math scores on the SAT are half of your overall score, while on the ACT they make up 25% of your overall score.

ACT math questions have 5 answer choices, while SAT math questions have 4. This means your chances of guessing the correct answer are higher for SAT math questions (25%) than ACT math questions (20%).

The SAT has some math questions that are fill-in-the-blank, while the ACT math section is all multiple choice.

With test differences in mind, you can assess how your strengths and weaknesses line up with what you now know about the SAT and ACT.

You fear or strongly dislike science

You tend to need more time to answer questions on tests

You don’t feel as comfortable with advanced math topics

You feel comfortable with math word problems and data analysis

You love science and feel that interpreting scientific data, charts, and graphs is one of your strengths

You have no problem working through problems quickly on tests

You’re strong in math, especially geometry

The ACT is now given internationally as a computer-based test only. Students who live outside of the U.S. (including U.S. Territories) or Canada should take this into account, as many students benefit from being able to underline, circle, and take notes on the test booklet.

The first few times I did tutoring online were completely by chance: one student’s family moved away and she wanted to continue SAT tutoring. When I realized how well virtual tutoring worked (in some cases, even better than in-person tutoring), I decided to make the switch and work with all of my students online.

Over the years I’ve noticed that some parents are completely comfortable with the idea of virtual tutoring, while others many parents aren’t sure how it works. Having done both in-person and online tutoring for a number of years, I wanted to share how online tutoring works and discuss some of the advantages and disadvantages of each approach.

Check out this infographic for a comparison of virtual and in-person tutoring. Credit to Kristin Craig.

Online tutoring can be done using a number of different modalities and technologies, including one or more of the following: video call (FaceTime, Skype, Google Hangouts, Facebook messenger video, etc.), online chat (text chatting, such as Gchat in Google, or Facebook messenger, etc.), email, online whiteboard applications, Google Documents, phone, text, photos, and many more.

I generally connect with students using Google Hangouts, which is a free video call function that allows for screen sharing. Anyone with a gmail account can use Hangouts, and there is even a Hangouts phone app.

Both during and between tutoring sessions, students and I may exchange photos of work and texts/emails with questions and explanations. Since Google Hangouts allows for screen sharing, if students are working on something on their computer (an essay, for example) they can share their screen with me so we can look at the work together. If we are using another video call application that doesn’t have screen sharing capabilities, students will just email me their documents.

For math (or science that involves equations and math operations), students will either send me photos of their work or email me documents if the work is available in digital form. We then talk through the steps and show each other on the camera (by writing on whiteboards or even notebooks with marker). We can also write in the Gchat chat box as needed.

Convenience. All that’s needed is a computer or tablet with an internet connection.

Efficiency. Student/tutor doesn’t spend time/resources getting to and from tutoring sessions.

Students gain familiarity/expertise in working with technologies that are increasingly used in the workplace.

Independence and ownership. Students are responsible for knowing what they need to work on and sending photos or links for any work to the tutor prior to the tutoring session.

Students/tutor are connected in real time and use technology to share and edit documents, work through problems, and review steps in real time just as they would do in person.

For math/science, students work independently while talking through their problem solving steps (instead of the tutor watching and intervening, as with in-person tutoring). Explaining/verbalizing their processes helps students become better problem solvers.

Students and tutor may never meet in person. Some people may feel that the relationship is “less personal.”

Some students who have major issues with organization may benefit more from in-person, hands on guidance to improve their organizational skills.

Temporary internet or technology failures may require rescheduling of tutoring. (However, this can be compared to cancellations of in-person tutoring for illness, bad weather, transportation issues, or other causes.)

Possibility of distraction. Just like in-person, in-home tutoring, parents need to set aside a quiet place for students to do virtual tutoring.

Access to technology. Although many students have access to computers or tablets at home, lack of these resources makes virtual tutoring more difficult. (One solution is for students to stay after school and use their schools’ computer or technology labs for virtual tutoring.)

Please let me know your thoughts on virtual or in-person tutoring in the comments below!

If you’ve decided that your child would benefit from tutoring, how do you go about finding a great tutor and making sure he/she is a good fit for your child? With so many companies and individuals offering tutoring services, it can be hard to know what will work best for your student. Word to the wise: tutoring is not a one size fits all scenario. It’s best to carefully think through what your child would benefit from and let that guide you in finding a great tutor.

Here are a few questions to reflect on that will help you identify what you’re looking for in a tutor.

Does my kid need help in just one subject area or several? Would it be helpful to have a tutor who is experienced/knowledgeable with different subjects?

Does my kid have specific learning challenges that I’d like a tutor to be familiar with/sensitive to?

Is time/convenience/transportation an issue? Does my kid feel comfortable with and enjoy using a computer? Would virtual or in-person tutoring be a better fit?

Does my kid struggle with organization, remembering and meeting deadlines, and/or study habits and skills in general? Would it be helpful to have a tutor who is well versed in these common academic issues and able to propose solutions?

Does my kid lack confidence in a subject or school in general? Would it be beneficial to work with a tutor who understands these issues and can help my child build his/her academic confidence?

With your child’s needs better defined, you can now identify potential tutors. A great tutor will have the following qualities:

Experience tutoring, teaching, coaching, and/or working with kids

Personable and easy to communicate with

Expertise/experience with the subject matter

A growth mentality (focused on improvement)

Caring and invested in students’ progress

A holistic approach that seeks to build study habits and academic confidence

While there are many companies that offer reasonably priced tutoring, both in person and online, from my experience I strongly recommend choosing a person, not a company that will assign one or possibly a revolving door of (often poorly paid) tutors to work with your kid.

As a former classroom teacher and longtime tutor, I’ve become familiar with the hiring practices and approaches of many tutoring companies, and I believe that parents are better off going with a well-qualified individual tutor who works with a handful of students than a company whose business model depends on having hundreds or thousands of students (and tutors) on its roster. Successful tutoring is highly personal: it starts with the rapport between your child and a caring tutor who’s invested in your child’s academic growth.

We all probably remember that one teacher who was a subject matter expert but whose explanations went right over our heads. There’s a huge difference between knowing a topic well and being able to break it down in a way your kid can understand and master. Having a background in education helps, but good teaching is both a science and an art. A great tutor can break down a complicated topic and effectively reteach it to your kid. A great tutor can also get right to the heart of your child’s academic challenges (Is it just difficult material or are there gaps in skills from previous years? Motivation/study habits issues?) and start addressing them.

I’ll discuss this topic more in a later post, but here is a helpful infographic to break down the differences between online and in person tutoring. Infographic courtesy of Kristin Craig.

Where to Look

You can start by asking around: ask your kid’s teachers or school administrators (note that some schools have a policy prohibiting tutor recommendations), ask other parents, ask neighbors, etc. You’ll probably get some great recommendations. If not (or in addition), you can look online on freelance sites like Upwork, Guru, Craigslist, etc.

It’s always best to meet with potential tutors face to face, or via video call (FaceTime, Skype, Google Hangouts, etc.) prior to setting up tutoring. If that’s not possible, exchange emails, texts, or have a phone conversation to get a feel for their communication style and personality. Hire a tutor only after you feel comfortable that person is a good fit for your child.

Do you work with students in-person at an office, in students’ homes, or online?

What subjects and grade levels are you comfortable with and experienced in tutoring?

Do you have a background in the field of education? Have you worked with (elementary, middle, high school) kids?

How would you describe your approach to tutoring? (Look for someone who has an individualized, holistic approach.)

If applicable: have you worked with students with special needs or learning challenges? (Not necessarily a deal breaker if the tutor seems open to learning about it and otherwise seems like a great fit.)

If applicable: do you work with kids on improving their organization or study habits and skills?

What are your payment and cancellation policies?

When or how often do you communicate with parents? (Look for someone who seems open to communicate with and involve parents as needed.)

Based on a detailed description of my child’s difficulties, how many days/hours of tutoring would you recommend per week? (This is of course ultimately your decision as a parent, but it’s helpful to hear what an experienced tutor recommends.)

If you found this article helpful, please feel free to share on social media and tag me in the post. Parents, please let me know if you have any other questions or would like to share any experiences in the comments below!

It’s sometimes hard for parents to know when it’s time to get outside help for their struggling student. Answer the questions below (taking your time to reflect honestly on your child’s academic situation) to see if your child may need tutoring.

Are your child’s grades in a class (or across all subjects) consistently lower than you believe his/her abilities and potential would suggest they should be?

Does your child feel upset or anxious about a class or about school in general?

Does your child verbalize or demonstrate that he/she believes statements such as: “I’m just not good at ____ [class, test taking, school in general].” “I’m not one of the smart kids.”?

Does your child often lose or forget to do homework assignments and/or generally lack organization and accountability for school work?

Is it difficult for you to help your child academically (due to difficulty of material, time constraints, conflict that arises when you try to help, etc.)?

Do you feel that your child would benefit from enrichment activities because he/she isn’t being challenged enough at school?

Does your child seem to lack motivation and/or the appropriate effort in a particular class or school in general?

Does your child seem to know the material but performs poorly on tests/quizzes?

Does your child have academic skill weaknesses or any diagnosed learning difficulty?*

Do you feel that your child would benefit from having someone outside your family provide academic support and guidance?

*For question 9, if your child has been diagnosed with one or more learning issues and is receiving adequate support at school, you can answer “no.”

If you answered “yes” to one or more of the questions above, your child may benefit from academic tutoring. The more “yes” responses, the greater the likelihood that tutoring would help your child.

In my experience as a tutor (primarily working with students in grades 6+), many parents report that their kids’ academic difficulties began in grades 3-6. Other tutors I’ve spoken with feel that grades 3-4 are when many academic weaknesses start to show up. If unaddressed, these weaknesses often continue to cause students to struggle throughout middle and high school.

I’ve come to believe that it’s best for kids to get help as soon as they begin to have difficulty (rather than taking a wait and see approach) in order to build proficiency and confidence with the skills they’ll need for higher grade levels. I’ve found this especially true for math, which builds upon previous skills with added complexity year after year.

In a separate article I’ll discuss what to look for in a tutor.

One of the things that I love best about writing curriculum is that I get to think about what I would have loved to have when I was in the classroom. I’m also fortunate enough to see things through the eyes of the kids I tutor: which skills and areas often need reinforcement? What motivates and interests them? What academic skills will they need as they move through middle and high school into higher education?

An issue that consistently comes up for many of the kids I work with is writing. Being a sticky skill, it’s one that takes time to improve. It also generally takes a multiple-pronged approach, with improvements in vocabulary and word use, grammar, mechanics, transitions, and logical sequencing of ideas. While “more writing” may help with fluency, it doesn’t do much to address the other issues that contribute to weak writing skills.

My goal was to create a daily writing resource that is targeted at improving the component skills of writing. I also wanted to incorporate deep reflection and analytical thinking about “the big questions” to spark intellectual curiosity and broaden horizons.

I think the best use of this resource is as a daily class starter, since the benefit of reflection and deep thinking will carry through class. Alternatively, it could be given as daily homework. The writing prompts and vocabulary/grammar tasks should take about 10 minutes to complete individually. I included ideas for optional collaborative work as well.

Each quote includes biographical and historical information to provide context, and vocabulary/grammar notes to call attention to specific vocabulary and grammar topics. One or two short vocabulary or grammar tasks are given as well. Next, the writing portion is divided into two sections. Under “Analysis,” students will analyze and explain the meaning of the quote. Under “My Thoughts,” students will state whether they agree, disagree, or partially agree/disagree with the quote and explain why using at least one concrete example that proves or disproves the validity of the quote.

While this resource is truly no prep, I would recommend (before students begin to work with it) taking some time to go over the example response provided. This will help students understand the difference between the two writing tasks: analyzing and explaining the meaning of the quote and then giving their opinion and backing it up with examples.

The resource includes different options for grading and a rubric for formal grading if teachers elect that option.

Check out a preview of the resource and purchase it here and as always I love to hear your feedback!

The recent passing of Toni Morrison has had me reflecting about why exactly representation matters so much in literature (and all of the arts). The most frequently cited reason is that kids and adults need to see themselves and their experiences reflected in a variety of ways that are not limited by stereotypes. But representation also helps expand our empathy through deepening our understanding of the human experience and allowing us to identify with and feel for others who, on the surface, may appear to be quite different from us. In a world that so urgently needs more compassion, this is a powerful reason that representation is so important.

If you can only be tall because somebody’s on their knees, you have a serious problem.

—Toni Morrison

My mom gave me Morrison’s The Bluest Eye when I was 13 years old, and reading it was completely transformative. It was the first book I’d read about a black character by a black author. It profoundly shaped my development as a white girl previously unaware of racism and the experiences of black people in America. I could have continued to go through life with my eyes closed to other people’s struggles, but thankfully Morrison’s words touched me and sparked a lifelong quest to expand: my empathy, my understanding, my knowledge of history, and my desire to help. Seeing the world through Pecola’s eyes also expanded my awareness of gender: the fact that certain experiences are unique to girls and women by virtue of being girls and women is something that many of us understand unconsciously, automatically, but without the consciousness that allows us to see the possibility of a better way.

There seems to be such a thing as grace, such a thing as beauty, such a thing as harmony. All of which are wholly free and available to us.

—Toni Morrison

Throughout high school and college, I continued to choose to read a wide variety of authors, and in every great book there were characters I cared so deeply for, no matter how different they seemed from me. When we care about fictional characters that seem very different from us, when we strive to understand their experiences within the context of the larger society in which they live, it becomes easier to understand real people with real experiences in an unjust world. It becomes easier to see clearly our position in that world and use any privilege we may have to help deconstruct racism and sexism and stand up for justice.

“I tell my students, ‘When you get these jobs that you have been so brilliantly trained for, just remember that your real job is that if you are free, you need to free somebody else. If you have some power, then your job is to empower somebody else.”

—Toni Morrison

Our kids need Morrison’s words and the words of so many other writers. Because our kids need to see themselves reflected in empowering or relatable ways, yes, but also because empathy expands when it extends to characters who we otherwise may perceive as “not like us.” Literature is a powerful tool in building empathy, and empathy is what we so desperately need more of in this world. RIP Toni Morrison, your words were a gift that will live on.

As teachers, we have quite a bit of control over how we teach topics to our students, the activities we give them to enhance learning, and the preparation materials we give out before unit tests, midterms, etc. But we don’t have much control over what students do with what we give them as soon as they leave class for the day (and sometimes even in our rooms). Some students seem to know instinctively how to assimilate the new information and skills they learn in class, while others have parents who give them helpful study tips and fill in any blanks in their understanding. But unfortunately, others leave class confused about the topics covered and lack the tools (or the sense of agency) to improve their understanding.

While teaching learning strategies is often left to the realm of special education, in my experience most students benefit from gaining some insight into their own learning habits and practices. In fact, I think teaching kids how to learn is equally if not more important as teaching them what to learn. As a former classroom teacher turned tutor, I’ve realized that by giving kids insight into their own learning process we are setting them up to be able to approach future material confidently and to learn it successfully throughout their lives.

My goal in tutoring is to help students develop skills and habits that eventually make tutoring unnecessary, and I’ve found that one of the most powerful ways to do that is by getting them into the practice of being self reflective about their own learning. And it doesn’t take much in the way of formal teaching; with a series of questions and mostly student-driven discussions students become much more conscious of their approach to learning and about specific strategies that they can use to learn more effectively.

Clearly, one-on-one discussions with students are a great way to help them reflect on their learning, but unfortunately the classroom setting doesn’t give us much one-on-one time. I wanted to find a way to bring this beneficial practice into the classroom, so I’ve created this no-prep student self-evaluation that teachers can use and reuse throughout the year to get students thinking about the way they learn.

There are also some general principles about learning that are supported by research that we can pass along to students (informally, no lesson required). One is “distributed learning” (aka the spacing effect), meaning that learning is much more effective when studying is broken into smaller chunks over time than when crammed. This is especially helpful for students who have attention difficulties and may feel frustrated or bad about their need to take breaks while studying—the research shows that this is actually a better way to learn!

While old adages about studying may have said “use a familiar and comfortable study spot,” studies have shown that learning is actually enhanced when the surrounding context is varied. This means that studying in different locations, listening to different music or a variety of background noise, and with any other environmental variations can actually be beneficial.

Another learning strategy shown to be extremely effective is testing or “retrieval practice.” After spending some time studying the material, it’s best to put it away and see if we can recall it. Retrieval practice can include a formal in class assessment, or a homework assignment, but quizzing ourselves or having someone else quiz us is a great learning strategy that is supported by many studies. In How We Learn, author Benedict Carrey summarizes what’s been learned from research on retrieval practice in a 1/3 to 2/3 rule: the fastest way to learn something is to spend 1/3 of your time memorizing it and 2/3 of your time reciting it from memory.

Testing is studying, of a different and powerful kind. —Benedict Carrey

I find it helpful to share these types of strategies with students whenever possible, since it can help them make their study time more efficient.

Here are some questions that I want my students to be asking themselves in order to become more conscious of their learning habits and strategies. I usually take them through these types of questions a couple of times initially, and then I just remind them to ask themselves periodically.

How did I learn about this topic initially (lecture/presentation, assigned reading, activity, research project, etc.)?

How actively did I participate in the initially learning? What grade would I give myself for my efforts? (paying close attention, taking notes, completing the task well, reading carefully, asking questions, etc. vs zoning out, doing the minimum, skimming/skipping the reading, letting others do the work, etc.)

How much did I learn (as a percentage of what I need to know or be able to do)? What grade would I give my current understanding of the topic?

Could I explain the topic thoroughly to someone who knows nothing about it? Could I show someone step by step how to solve this type of problem or complete this task successfully?

What methods usually work best for me to learn something new?

What tools, resources, and practices can I use to get my knowledge/skill set to 100% with this topic?

Here are some steps to take students through in order to help them evaluate their own understanding of a topic. These can be used in any subject area.

Identify the topic as specifically as possible.

State what we know, what we don’t know, and what we need to know, keeping in mind that as we proceed we may uncover more aspects of the topic that we don’t know about

Identify the learning method: lecture with slides? Assigned reading? Research project? Informational video? Etc.

identify other learning methods/tools/resources that might be helpful or have been helpful in the past: asking the teacher for help, asking a friend, watching a video online, reading more online, rewriting my notes, doing additional practice, etc

Evaluate how much we know now: 50%? 75%? 100%? Etc.

Repeat the steps until understanding is at or near 100%.

I think self-reflection is one of the most important practices that we can pass along to students. Becoming more reflective about our own learning habits and strategies, as well as taking ownership over our learning, is a lifelong skill with so many benefits. I’ve created a resource that can be used with students in grades 6+ in any subject area for this purpose. It has three different self-evaluations: pre-semester, pre-assessment (to be used at the end of a unit but prior to a unit test), and post-assessment (for students to reflect on their learning during the unit and their preparation for and performance on the unit test).

Click on the photo below to get this resource and please let me know what you think about teaching learning strategies and self-reflection about learning!

I have my feelings about high stakes academic testing, and chances are you have yours as well.

On the one hand, the fact that individual students with all of their diverse talents and gifts are subjected to a single test that carries so much weight troubles me. I’ve seen first hand the anxiety that many students experience over their SAT and ACT scores. I’ve also seen the inherent disadvantages that some students face in taking the SAT/ACT.

On the other hand, I recognize that colleges need some “objective” method to both assess students’ readiness for college and compare students who may have almost identical academic records. Whether or not the SAT and ACT effectively meet this purpose is, of course, subject to debate. Studies have shown that students from wealthier and more educated family backgrounds tend to do better on the SAT and ACT than those from less privileged backgrounds. The SAT’s new adversity score attempts to contextualize students’ SAT scores based on their school, neighborhood, and home environments.

But for now, unless we opt out of testing (as some schools have allowed), SAT and ACT scores remain important factors in college admissions decisions. And if students are going to take them, they might as well give themselves the best chance possible of getting a high score.

There are many options for SAT/ACT prep, ranging from almost free and self-directed to pricy online and in-person courses and private tutoring. The good news is that with a solid study plan, some SAT/ACT materials, and consistent practice over a long enough period of time, students can improve their scores significantly without expensive SAT/ACT prep courses or private tutoring.

The skills tested on the SAT/ACT can be loosely grouped into content knowledge and academic skill.

Content knowledge is the specific material learned by students in a subject area, such as point slope form, special right triangles, and vocabulary.

Academic skill, on the other hand, consists of students’ abilities that apply across various subject areas (e.g., reading speed and accuracy, the ability to analyze a text for structural features, applying content knowledge to solve unique and unfamiliar problems, etc.).

There are some SAT/ACT questions that students could get right based on content knowledge alone. But the majority of questions involve academic skill of some kind, and without that the content knowledge only goes so far.

Content knowledge is relatively fluid. A student who has forgotten the rule for 30-60-90 triangles can relearn that rule pretty quickly. But academic skill is sticky; it takes a long time and a lot of practice to build.

Content may be learned, forgotten, and relearned, but critical reading, writing, and problem solving skills follow students throughout college, higher education and beyond, paving the way for better understanding and better academic performance. A longer view of SAT/ACT prep takes the approach of building these skills over the time necessary for them to become engrained, resulting in higher scores and better preparedness for more advanced studies.

So what’s the best way to prepare for the SAT and ACT? Aside from intensive prep courses or private tutoring (which can improve students’ scores in a relatively short period of time, at a high cost), the best SAT/ACT prep approach is an early start with a slow and steady pace to build academic skills like critical reading, writing, and logical problem solving. (Guide to Self-Study for the SAT/ACT)

I recommend that students take the PSAT or PreACT as early as possible and look to fill in any weaknesses as identified by one of these tests. I also recommend that students begin a regular vocabulary building practice as early as 8th or 9th grade, since a broad vocabulary is a major advantage in both the Reading and Writing/Language sections (and of course in college and beyond).

The single best form of preparation for the Reading and Writing/Language sections of the SAT and ACT (and for higher education) is being an avid reader. Students who love to read outside of their assigned school work tend to be more analytical and efficient readers and have better vocabulary, grammar, and writing skills.

While expensive SAT and ACT prep courses and private tutoring abound, diligent and self motivated students can improve their SAT/ACT scores with just a few affordable materials and a lot of practice spread out over as many months as possible. Check out this guide to self-study for the SAT/ACT for tips on how to prepare for these exams the right way, as well as the following resources for SAT/ACT prep:

Tons of free practice and full length tests for the SAT at Khan Academy

College Board Official SAT Study Guide 2020 Edition or 2018 Edition (Amazon)

Official ACT Prep Pack 2019-2020 Edition or Prep Guide 2019-2020 Edition (Amazon)

There are also many SAT/ACT prep books available from established test prep companies such as Kaplan and Princeton Review. These books recommend specific strategies for approaching different types of test questions.

I’ve also created the following resources that students can use independently for SAT/ACT prep:

Vocabulary for the SAT/ACT with tons of activities for better retention

Homophones and frequently confused words (often tested on the SAT/ACT)

SAT Math Formulas (FREE)

I think SAT/ACT self-study can yield great results for students who are disciplined, self driven, and consistent in their approach. For students who need more structure or have a short window before the test, the best option is to take an SAT/ACT prep course or schedule regular tutoring.

This is a general guide to self-study for the SAT and ACT without taking budget or time frame into consideration.

The first step in any SAT/ACT study plan is assessment. Students should take a full length exam and score it (if necessary to manually score) to determine where they stand prior to studying. Simulate real test conditions as much as possible to get the most accurate assessment of performance. The PSAT or Pre-ACT are pretty good predictors of SAT and ACT scores, respectively, but it’s best to take a full length SAT or ACT.

Khan Academy offers full length SAT’s online, plus students can link their College Board account with Khan Academy to input their PSAT and get personalized study recommendations.

Section scores and subscores will tell a story about students’ current levels of preparedness. For example, a student who takes a full length SAT and gets a 700 in math and a 500 in reading and writing clearly has to focus his or her efforts on the reading/writing sections.

Within sections, both the SAT and ACT provide score information for the different categories of questions. Students should spend some time going over their scores and looking at the specific categories of questions within each section. Students should also spend some time becoming familiar with the test format and how the test is scored.

If other testing issues arose, such as time management, students should take note of them as well.

Determine what kind of improvement is needed overall and across different sections of the test.

If students have a long window to study, score improvements of 300-400 points on the SAT and 10-11 points on the ACT are possible (I’ve worked with students who’ve improved this much!). The shorter the time before the test date, the harder it will be to get large score improvements, but solid score improvements are still very much possible. Set a reasonable but challenging goal.

Get materials with tons of practice problems, and content review materials for any subject areas that were especially weak. Here are the materials that I believe are essential to prepare for the SAT/ACT:

College Board Official SAT Study Guide 2020 Edition or 2018 Edition

Official ACT Prep Pack 2019-2020 Edition or Prep Guide 2019-2020 Edition

The College Board and ACT both make free practice questions available on their websites as well. Khan Academy also provides excellent free SAT study materials, including practice questions divided by topic. In addition, there are many other high quality study materials and online courses available, budget permitting.

The large test prep companies such as Kaplan and Princeton Review also offer workbooks and other SAT/ACT prep materials.

I’ve created the following resources specific to SAT/ACT vocabulary, grammar, and math that may be helpful for students:

Vocabulary for the SAT/ACT with tons of activities for better retention

Homophones and frequently confused words (often tested on the SAT/ACT)

SAT Math Formulas (FREE)

First, students should map out the time until the test date and break that time into weeks or months, whatever makes the most sense depending on the time period. Next, they should determine what they think they can accomplish during week 1/month 1 and each additional time period.

For example, students with low math scores would first need to spend a good amount of time reviewing math content. Unless a student scores over a 600 (or 25), he or she should review the content first and then start doing practice. If there’s still a year before the exam, students can spend a month reviewing math and any other content they might need to review. With only a couple of months to study, students can spend a week or two reviewing content.

Within the time period allotted for content review, students should break down the content further into chunks so that they have a day by day and week by week plan.

The ideal SAT/ACT study plan will have students doing something every day, even if it’s only for 15 minutes. The importance of consistency in studying for these tests can’t be overstated.

It’s far better to do 30 minutes a day of practice questions than 3.5 hours one day a week. That’s the same amount of total time spent, but there’s much more bang for the buck with the 30 minutes a day plan. The brain needs time and familiarity to assimilate everything that is learned in preparation for the SAT/ACT, and 3 hours one day and then nothing for 6 days just doesn’t cut it.

After doing any necessary content review, the majority of students’ study time should be dedicated to doing practice questions, analyzing why they got them right or wrong, and filling in any content gaps as necessary.

If there’s a year to study, students might spend a couple of weeks just working on one subject and really mastering it. With only a couple of months, students should spend no more than a few days doing practice questions in just one subject area.

As the test date approaches, students should mix the practice questions so that each test section gets some attention almost every day. The key is not to let any area get rusty before the test date.

Students should plan to take as many full length practice tests as they can, with at least a few weeks in between each full length test. Over the course of a year, students can easily take at least 4-6 timed, full length tests. If students have only a couple of months, they should try to take a full length test every 3-4 weeks. Also, they should set aside time to do regular timed sections in any weak test areas.

Language building involves forming as many connections in the brain as possible so that new words are understood in concert with other words, ideas, and even visual representations.

Read MoreAs someone in an “ally” position as opposed to a perceived authoritarian, I’ve also been able to gain some insight into students’ motivations, their perspectives on school, teachers, assignments, etc., and their perception of themselves as students.

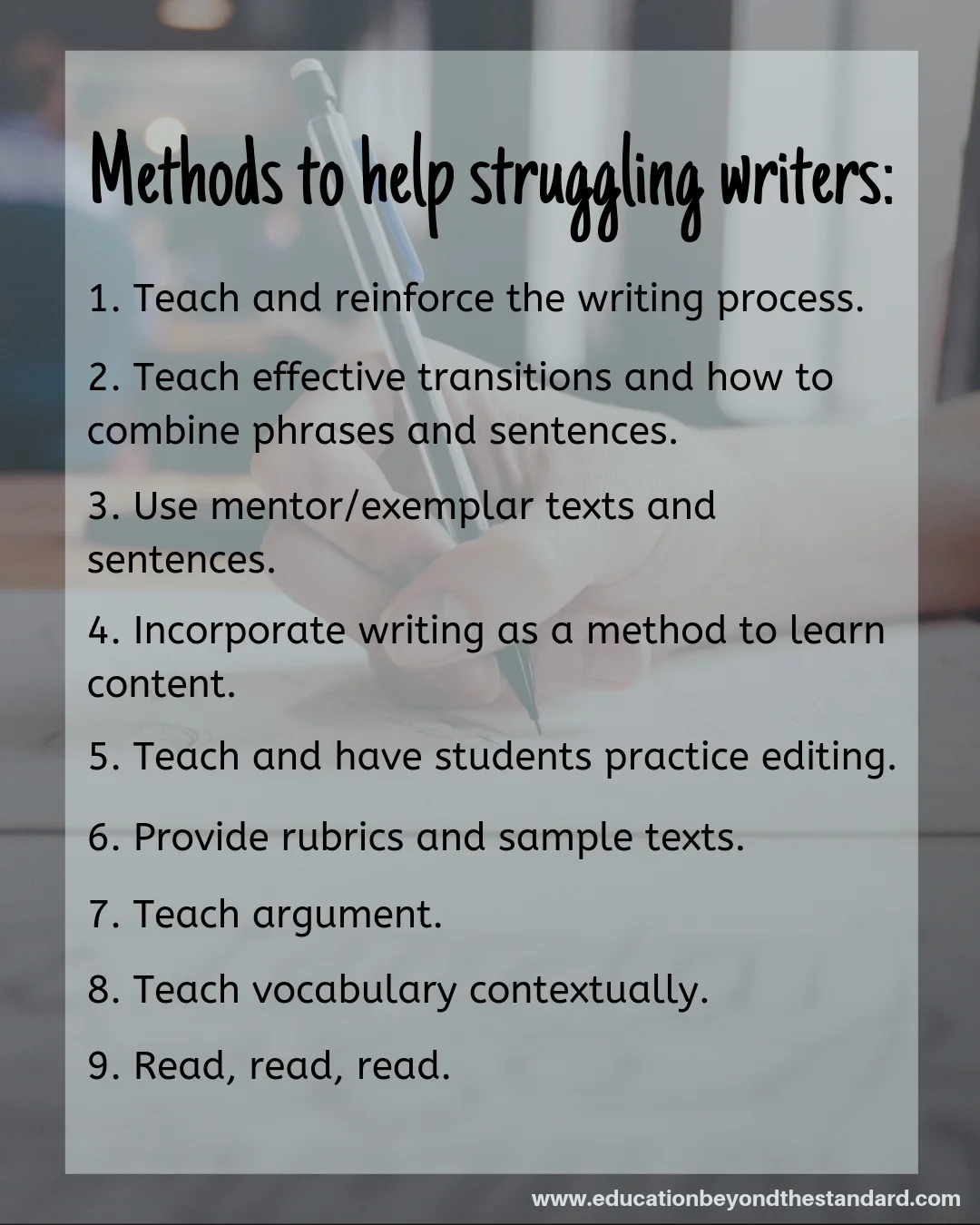

Read MoreIn a previous post, I talked about some of the similarities I’ve noticed in working with struggling writers. Now I’d like to share some methods for working with struggling writers that I’ve learned from personal experience and from the research on effective methods to improve student writing.

This point can’t be emphasized enough. While some stellar writers may instinctively use an effective writing process, the vast majority of our students will need specific instruction. Beyond teaching the steps of the writing process (Prewriting, Writing, Revising, Editing, Sharing), we need to teach students how to execute each step. And this requires practice.

Consider having students regularly outline essays in response to prompts in order to practice Prewriting. Make sure the outlines follow a logical structure and contain sufficient detail, as opposed to just brainstorming (which can be fine as an initial step in the Prewriting stage). Editing tasks and peer editing are good practice for editing and revising students’ own work.

Struggling writers often have difficulty putting together pieces of information (or arguments and supporting facts) in a logical and coherent way. Specific instruction on transition/linking words and phrases and how to use them is crucial to helping student writers.

Mentor texts and sentences illustrate the principles of writing and grammar that we’re teaching. Mentor sentences can be a great way to teach grammatical concepts and effective transitions. Also consider providing exemplar texts when you give a rubric (see below).

Writing about recently learned content has repeatedly been found effective in increasing retention and understanding. I’m a big believer in bringing writing activities into all subject areas, including math, science, and social studies.

Writing can be used across subject areas to:

reinforce content (“explain,” “summarize,” etc.),

make connections (“how is this material connected to [current events, something we learned previously]?” etc.), and

engage critical thinking (“why is this relevant/important?” “what else can we learn about this topic?” etc.).

Having tutored students in math for many years, I’ve noticed that when students can summarize or explain a process in writing they almost always achieve mastery with that topic. Incorporating writing wherever we can and across subject areas increases content understanding and provides even more opportunities for writing practice.

I can’t count the number of times I asked a student to edit his or her own draft, only to have the exact same draft returned to me with a few minor errors corrected. It took time for me to realize that many struggling writers don’t know intuitively how to edit their own work (or the work of others). Editing, just like writing, is a skill that must be taught. Students need to learn what to look for and how to look for it, as well as how to fix problems with sentences, paragraphs, or whole pieces of writing.

One of the best ways I’ve found to teach editing is by having students practice editing a text with defined numbers and categories of errors. By telling students how many errors there are within a certain category (like punctuation, verb tenses, etc.), we are training them to focus on the details that they otherwise may have skipped over. While zooming in to the grammatical details is important, we also need to teach students to zoom out to the big picture (the structure, strength of argument and supporting facts, etc.). Mentor texts are a great way to illustrate “big picture” qualities of writing.

One of the many great things I learned while tutoring students for the SAT/ACT was the value of sample texts in addition to a rubric. Many of the SAT/ACT study books contain sample student essays with a given score according to the general rubric provided. Reading a high-scoring essay and a low-scoring essay with the rubric as the backdrop is an impactful way for students to understand a grading rubric.

All too often, students eyes’ glaze over while reading rubric measures such as “arguments and supporting evidence are presented cohesively.” Providing sample essays on the highest and lowest end of the rubric and requiring students to read them (or even better, reviewing and discussing them in class) is a powerful tool to help students understand what constitutes a great piece of writing.

Argument and persuasion are often confused, but they are actually quite different. Argument can serve as persuasion, but persuasion requires much less in terms of reasoning. Argument is rooted in fact and logic while persuasion is rooted in opinion and emotion. Argument is essentially a truth-seeking endeavor, while persuasion is focused on, well, persuading.

I believe that we should prioritize teaching argument over persuasion, and that argument should be made a much bigger part of all school subjects. The process of argument (gathering evidence, making a claim, connecting the claim to the evidence, examining evidence to the contrary, and refining the claim accordingly) develops critical thinking and logical reasoning skills, which are part and parcel of thoughtful, coherent writing. These skills are also extremely important outside of academics.

While struggling writers often lack a broad vocabulary (or frequently misuse words), great writers tend to have great vocabulary and make effective word choices. Far beyond memorization of definitions, teaching vocabulary with a language building approach can have a great impact on students’ writing skills.

Vocabulary study with a language building approach is a holistic process that not only enriches students’ writing with greater variety of word choice, but also improves their grammar and their contextual understanding of language. Students learn words in context and practice using them correctly while also practicing good grammar. They learn to use different word forms (ex: meticulous, meticulously, meticulousness) while developing a better understanding of sentence structure.

Studies have consistently supported a correlation between increased reading and better writing skills. The same goes for the link between reading and vocabulary and other cognitive skills. There is no question that reading provides great intellectual and emotional benefits, so the more we can have students read the better.

Outside of assigned reading, here are some ideas for encouraging and incentivizing student reading:

1) give an optional reading list (during the year and/or over breaks) with prizes for completion

2) set up a “Twitter style reading board” where students add “tweets” about the books they’re reading

3) host a student book club or create small group book clubs that select a book and meet once a month

4) hold a class reading contest or class vs. class contest

5) give an optional reading list from which students choose several books and complete book projects

6) maintain a classroom library with a diverse selection of fiction and nonfiction

7) allow in-class reading of student selected books when students complete class work

8) create an Instagram-style board where students post photos inspired by what they’re reading with captions that relate the image to the text

9) hold a “books made into movies” seminar—students read/watch and discuss which version was better

I’d love to hear what methods you’ve found effective in helping students improve their writing skills!

The importance of good writing skills can’t be understated. While in some respects media and technology advances have changed the way we write (e.g., the prevalence of short statements as in tweets and social media captions, etc.), writing remains a fundamental form of human expression and transmission of ideas.

Despite educators’ best efforts, however, research indicates that a troubling percentage of students graduate from high school with poor writing skills and/or unprepared to write at a college level. Recent studies have shown that up to 3/4 of students across different grade levels lack proficiency in writing.

As teachers we know how difficult it can be to improve students’ writing skills. After all, there is so much that goes into good writing! And just as poor writing skills didn’t develop overnight, strong writing skills take time to develop.

Before looking at some research backed methods for helping students become better writers (in a separate post), I’d like to share some of the patterns and tendencies I’ve noticed in working with struggling writers over the years, both as a former classroom teacher and now tutor.

When asked to state the main idea of passage, describe its structure, analyze the development of an argument or theme, etc., struggling writers tend to give vague or unclear responses that are loosely supported by the text. It’s not surprising given that the same skills involved in good, logical, cohesive writing are required for analytical and critical reading. While reading and writing skills don’t go hand in hand 100% of the time, there is a large enough overlap that a weakness in one area typically predicts a weakness in the other.

These students may not be able to avoid using run-on sentences, for example, because they don’t actually understand what an independent clause/complete thought is. They might not understand on a fundamental level the role of the different parts of speech in a sentence. They might see that they’re getting marked off for the same things over and over again, but they aren’t able to make the connection and master the grammatical concepts involved.

These students tend not to read with an eye to detail and, as a result, they often miss all but the most glaring errors. Even when told that there are remaining punctuation issues, for example, they may be unable to find the errors.

It is often not obvious to struggling writers that the order of ideas has a huge impact on the coherence of a text. They tend to view ideas and information as discrete, somewhat related pieces rather than as part of an overall logical flow. When we point out a lack of logical sequencing or organization, they really don’t understand on a fundamental level why a particular sequence of thoughts makes more sense than another.

These students tend to have a limited working vocabulary, a poor understanding of the nuance and connotation differences between words, or both. They may be able to define a word but be unable to use it effectively in an appropriate context. They also tend to be repetitive in their word choice and unaware of redundancies in their writing. If asked to restate an idea in different words, for example, they often struggle to do so.

One of the biggest tendencies that I notice in the students who struggle with writing is that they usually don’t plan or outline their writing in advance. While some excellent writers can produce great essays without much advance planning, the majority of struggling writers start writing without an effective plan for organization and structure. They tend to resist the planning process unless it is made a mandatory part of the writing assignment (an outline required to be submitted, for example).

On the flip side, struggling writers may remain “stuck” in thinking about their writing assignments. They may have difficulty with writing fluency and knowing how to effectively start a piece of writing without significant prompting.

These students, more often than not, read very little, if anything, outside of what they’re assigned. With the prevalence of sites like Cliffnotes and Sparknotes, many reluctant readers scrape by without even reading assigned texts at all. (For better or worse, kids often tell me, their tutor, about the “shortcuts” they take.) They largely view reading as a task rather than a joy.

There are exceptions to all of the above, of course, and some struggling writers may have only one or two of these issues. In another post, I’ll address the methods I’ve found most effective in helping struggling writers.

Please let me know if you’ve noticed these or other issues with your struggling student writers!

Novel or nonfiction study is a great way to teach so many things: themes and symbolism, author’s craft and devices, literary analysis, and vocabulary too. But all too often, vocabulary gets relegated to a list with definitions that students memorize for a quiz or test...and likely forget soon after. Fortunately, it’s fairly easy to incorporate new vocabulary and language building activities into a novel or nonfiction study unit.

Read MoreMost kids (and adults) have dreams or ambitions of doing something. What often determines whether that something becomes reality is how we set ourselves up to achieve it. While of course some of our potential is influenced by what we get in the genetic lottery, a good portion of it is also the goals we set for ourselves and how effectively we direct our actions toward achieving those goals. It’s also influenced by how well we can work with our bad habits and replace them with good ones.

In short, effectively setting goals for ourselves and becoming more aware of our habits, good and bad, directly impacts the quality of our lives.

There’s no doubt that effective goal setting is a great lifelong skill, but there’s a lot of misunderstanding about how to set effective goals and the factors that influence whether they are achieved. While some learn good goal setting practices from parents, sports coaches, or music teachers, many of us get to adulthood without really knowing what good goal setting looks like. Imagine if we all learned about effective goal setting and habit change early in life!

I used to think of goal setting as one of those reflexive, automatic things that everyone knows how to do and does already. In my first year of classroom teaching I used to tell students, “set goals!” and think that was a meaningful piece of advice (sheesh). It hadn’t occurred to me that, for most of us, effective and meaningful goal setting doesn’t come naturally and needs to be learned.

As a tutor, I’ve realized that one of the most important tools I have to help students is to teach them effective goal setting. I’m now convinced that it’s something we should be actively teaching and reinforcing with all students.

Through effective goal setting, I’ve seen kids go from barely passing their classes to getting A’s and B’s and feeling good about school overall. I’ve also seen kids who had felt unmotivated and overwhelmed by school become focused and determined to achieve what they had set out to do. But it didn’t come from my telling them to “set goals.” It came from their understanding of what goals actually are and the specific steps needed to make goals into reality. It also came from their becoming more aware of their habits, good and bad, and how changing seemingly small habits is crucial to making bigger changes.

In order to help students become better goal setters, we need them to understand what effective goals look like, be able to break them into bite sized steps, and plan for any obstacles that may arise.

Meaningful goals are specific and measurable. The simplest way to think of this is whether the question “did you meet your goal?” can be answered with a simple yes or no. If not, the goal is not specific and measurable. Some goals may not lend themselves to setting a time limit, but when possible goals should include a completion time, like “tomorrow,” “for the semester,” etc. Once the time period passes, it should be easy to answer the question of whether the goal was achieved.

Next, goals need to be broken down into small and specific actions that are also measurable (yes/no). For example, if the goal is to complete a 10K run by the end of the month, the actions might consist of your weekly training schedule (week 1: run 2 miles 3x, etc.).

If the goal is academic (“get an A in History this semester”), the steps might be things like review my notes every day after school, turn in all my homework on time, keep a running vocabulary/terms list and update it at least weekly, etc. Like the goal itself, the steps must be specific and measurable in order to accurately assess their completion when reflecting back on the results of goal setting.

The next part is where people (especially yours truly) tend to fall down, unfortunately. Human nature is to procrastinate and avoid doing things that are less fun in favor of having fun. We think that by setting the intention to do something that we’ll be sure to do it, but as most of us probably know, it can be easier said than done.

We are also creatures of habit, and just as good habits can help us reach our goals, bad habits can make it more difficult for us to do so. Researcher and writer James Clear (check out his website here) writes that goals are like rudders, the things that give us direction, and systems are the oars, which actually get the work done. He also writes about the importance of habits in achieving goals, and specifically about how we can change our habits.

Effective goal setting requires consideration of the system that surrounds you. Too often, we set the right goals inside the wrong system. If you're fighting your system each day to make progress, then it's going to be really hard to make consistent progress.

There are all kinds of hidden forces that make our goals easier or harder to achieve. You need to align your environment with your ambitions if you wish to make progress for the long run.

—James Clear

By anticipating obstacles and challenges that may arise, we can prepare ourselves with a plan to complete our steps no matter what. This requires an honest evaluation of the types of challenges that may interfere with our achieving goals.

We can reflect on past experiences when we’ve set a goal and didn’t reach it for a number of reasons. We can also look at ways in which our environment can help us or hinder us in adopting the habits that help us meet our goals.

For example, I know that oftentimes I’ll get distracted with other projects or by texts or phone calls. So if I know I have to complete a step, I might plan to turn off my phone or put it far away until I finish. Or maybe I designate a specific time to complete the step so that nothing else can distract me.

I find it’s helpful for me to share with students some of my own obstacles and the ways that I deal with them in order to get them thinking about ways to better manage their obstacles.

After the goal’s time period has passed, it’s important for students to learn to reflect on what went wrong and what went right. This process helps them to better understand themselves and their strengths and weaknesses. It also encourages a growth mindset that is focused on progress and learning over perfection.

Reflecting on success or failure (and especially the process that led to either one) is also important in informing future goal setting. If we become aware that a bad habit prevented us from reaching a goal, we can work to overcome that habit and replace it with a better one.

If you’re interested in learning more about habit change, I recommend Atomic Habits by James Clear (Kindle version and audiobook), or you can listen to a great interview he did on The Psychology Podcast.

I’ve also created this no prep resource for teachers to bring goal setting into the classroom with a pre and post term goal setting activity.

Please let me know in the comments what you think about teaching goal setting, what works, what doesn’t, etc!

Powered by Squarespace.